"I-70 shutdown will echo 1999 event that aided minority, women-owned firms"

St. Louis — The news conference was meant to decry the lack of minority contractors on a bridge project, but it fell into disarray when one participant decided to climb onto a piece of construction equipment.

Others soon followed. And before that late June morning in 1999 was over, 31 people landed in a police lockup.

"After we got out that night, we decided we needed to do something bigger the next time," attorney and activist Eric Vickers recalled.

The day after the arrests, Vickers composed a letter to then-Gov. Mel Carnahan, threatening to block Interstate 70 in St. Louis if the state didn't do something to increase minority participation on highway projects.

And 10 years ago today, a coalition of contractors, politicians and civil rights champions made good on that threat, bringing Monday morning rush-hour traffic along the interstate to a halt. It was an act of civil disobedience that continues to reverberate within the local construction industry.

"Nobody wanted to shut down that highway, but it opened a lot of doors," said Thomas L. Nellums Sr., the owner of TEE & E Trucking in St. Louis.

Indeed, activists and state officials acknowledge that the I-70 protest in 1999 sparked numerous changes for the better. A construction training program initiated in the aftermath of the protest has produced more than 1,000 graduates. Including minority contractors has become common practice, not only for highway work but on other major capital projects involving various institutions — the St. Louis Art Museum, University of Missouri-St. Louis and BJC HealthCare among them.

"We are doing things now to build relationships with the communities that are necessary to head off (those) types of issues," said Lester Woods, the external civil rights director for the Missouri Department of Transportation.

But some believe more needs to be done, and they say a protest similar to the one 10 years ago may be the best way to make their point.

CIRCUMVENTING RULES?

An organization called the African-American Business and Contractors Association contends that some injustices have yet to be addressed, noting how contracts have been allocated for the construction of the new, $640 million bridge connecting Illinois and Missouri.

Federal and state guidelines for minority participation give African-Americans and women equal footing, but state data show that the vast majority (88 percent) of the contracts set aside for those groups have gone to women-owned businesses, not African-Americans.

African-American contractors contend that white owners often circumvent the intent of those rules by transferring ownership to their daughters or wives.

"How can you win when the system is set up to help companies, who have been in business for 30 years, get family members certified (for minority ownership)?" said Carmell "Mack" Macklin, owner of Macklin Hauling.

Frank Haase, a white contractor who is president of R.G. Ross Construction Company, is a member of MO-KAN, the St. Louis Construction Assistance Center. MO-KAN is a consortium representing minority contractors that played an integral role in the interstate shutdown 10 years ago.

Haase acknowledges that some businesses occasionally flout the rules for women-owned contractors, but he said the practice was not widespread.

Nonetheless, black contractors are asking Illinois and Missouri to separate minority-owned firms from female-owned businesses in awarding contracts for the Mississippi Bridge project.

To draw attention to their concerns, the black contractors plan to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the shutdown with another protest Monday morning at an undisclosed location along I-70. Organizers say they will not take any action that should result in arrests.

"We have issues with (the Missouri Department of Transportation). They're making progress, but they will have to improve," said Makal Ali, a protest organizer.

Some contractors, however, say a protest isn't necessary this time. MO-KAN will skip the I-70 demonstration.

"We are sitting at the table (with Illinois and Missouri transportation officials), and we haven't exhausted the means of getting to the place where we think we need to be," said Yaphett El-Amin, the group's executive director.

'NOT ENOUGH' CHANGE

After the arrest of 31 demonstrators in 1999, minority contractors and advocates held discussions with state officials. The talks extended into simmering resentment among minorities over a highway bridge project at Taylor Avenue.

"All this construction was taking place in the heart of the black community, and no blacks were working on the project," said Anthony Thompson, the president and chief executive officer of Kwame Construction. "Getting attention of the community and the nation was the only way we could change the situation."

The meetings got the attention of the community. Persuading the Rev. Al Sharpton to join the shutdown guaranteed a national audience. Still, negotiations eventually faltered.

"They knew we were going to shut down the highway," Vickers recalled. "They just didn't know how."

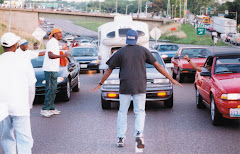

The plan called for vehicles driven by protestors to draw abreast of each other along I-70, gradually slowing eastbound traffic to a stop at Goodfellow Boulevard where other demonstrators, on foot, awaited.

It unfolded just as the organizers had hoped. An hour after the word to "move forward" sounded from a bullhorn, traffic began to flow again. There were no injuries.

All told, an estimated 300 people took to the highway that morning. Of those, 125 — including Sharpton — were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct.

A decade later, Vickers recalls the protest with pride. The community and the state did respond to the issues that were raised. More doors began to open for minorities.

But as Monday's protest approaches, Vickers says he's still not sure how he feels about it. Should he stand with the demonstrators? Or, should he stand aside, acknowledging that progress has been made and there are other ways to address inequities?

"It's changed," he said. "But just not enough."

Eric E. Vickers

Attorney, Minority Inclusion Alliance

St. Louis Metropolitan.

Sunday, July 12, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

,+W.+Bevis+Schock+and+James+Schottel,+Jr.+(seated)+claim+north-side+land+magnate+Paul+McKee+will+displace+residents+for+a+project+he+can%27t+possibly+pull+off..jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment