In 1980, the United States Supreme Court, in the case of Fullilove v. Klutznick, gave its stamp of approval to perhaps the most important piece of legislation affecting minorities in America in the last 30 years.

In upholding the constitutionality of the controversial provision of the 1977 Federal Public Works Act that set aside 10 percent of public dollars for minority businesses, the court spawned a national wave of minority economic inclusion, which swept through the federal procurement process and state and local governments.

U.S. Rep. Parren Mitchell of Baltimore, who sponsored the set-aside provision and later came to be known as the “father of minority business,” called this the final phase of the Civil Rights Movement: the economic struggle.

By the mid-80s, African Americans had begun asserting and seizing political power by capturing mayoral offices in major cities like Atlanta, Detroit, New Orleans, Chicago, Richmond and Washington, D.C. Governmental power was then leveraged to create economic opportunities through enacting laws and policies mandating that specific percentages of public contracts – generally, between 20 percent and 35 percent – be awarded to minority businesses.

In St. Louis, the aldermanic black caucus adopted a resolution in 1981 to require 25/5 percent inclusion of MBE/MWBE (Minority Business Enterprises and Women Business Enterprises, respectively) on any project with government subsidy. Though they could not get the requirement passed into City law, they did succeed in attaching it on a project-by-project basis, according to then Comptroller Virvus Jones.

Jones said the 25/5 percent inclusion concept was developed by the black members of the Board of Aldermen. Jones personally wrote and passed an amendment to the Cable TV legislation that required 50/50 black inclusion on jobs and contracts created.

“Vince was only using the formula created by the black aldermen when he agreed to the consent decree,” Jones said of Mayor Schoemehl’s 1989 executive order.

Still, St. Louis lagged behind most metropolitan areas with similar substantial minority populations. Despite the outspoken cries and efforts of Jones and other black elected officials, little organized community pressure had been brought as of late on the St. Louis construction industry.

But in 1988 a group of minority contractors went into battle, on both the legal and activist fronts, with the black media as their wings. At the core were five principal organizers of the 1999 I-70 Shutdown: Eddie Hasan, the visionary; Larry Ali (deceased), the strategist; Mikel Ali, the fighting spirit; Tiahmo Rauf, the master organizer; and Anthony Shahid, the brave heart.

Six campaigns

Six major protest campaigns over the past 20 years have come to define the minority inclusion movement in this town.

The December 1989 Federal Court Consent Decree in the lawsuit filed by the Minority Contractors Association established the City of St. Louis’ law and M/WBE program requiring 25 percent minority and 5 percent women participation on all City contracts, which still exists as the standard bearer for inclusion in the metro area.

The minority contractors campaign against the banking community to end discriminatory business lending – including the November 1996 protest on Wall Street, in which minority contractors chartered a TWA Jet to fly over a hundred protestors to New York – ultimately resulted in a $100 million lending commitment to the minority community.

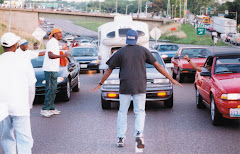

The July 1999 I-70 Highway Morning Rush Hour Shutdown Protest involving Rev. Al Sharpton, where over 100 protestors were arrested, resulted in the establishment of the Construction Prep Center (CPC) that has now matriculated and placed hundreds of minorities into the construction industry.

The spring 2003 campaign against Metro transit for minority inclusion on the $500 million MetroLink Project resulted in Metro agreeing to increase minority inclusion by, among other things, establishing separate goals for minorities and women on the project and breaking it down into smaller parts to enable minorities to bid as general contractors.

The spring 2005 campaign against IDOT for lack of minority inclusion on the McKinley Bridge and I-64 projects then in progress resulted in, among other things, the establishment in East St. Louis of a construction training program modeled on the Missouri CPC.

The fall 2005 Rosa Parks Initiative targeted and obtained inclusion on 11 major construction projects in the St. Louis area totaling over $3.6 billion over a five-year period, including the MODOT I-64 Project and the New Mississippi River Bridge Project.

In recent MODOT/IDOT Roundtable meetings over achieving minority inclusion on the New Mississippi River Bridge project, I have been impressed by the number and eagerness of a new generation of minority and women entrepreneurs who have been attending and raising important but familiar issues.

I think it important for them to know the history, including the history that need not be inefficiently repeated, in order that they can bring the freshness of their ideas and approach as the next layer in the movement.

While Atlanta deservedly has earned the reputation as the Mecca of minority inclusion, I know from having served as the Special Counsel to the Washington, D.C.-based Minority Business Enterprise Legal Defense & Education Fund, Inc., that the minority inclusion movement in St. Louis became renowned throughout the nation for its activist approach to economic justice.

“You cannot depend on American institutions to function without pressure,” said the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Any real change in the status quo depends on continued creative action to sharpen the conscience of the nation and establish a climate in which even the most recalcitrant elements are forced to admit that change is necessary.”

Attorney Eric Vickers prepared the above article for St. Louis American. Click the following link to read the article: Activist-attorney reflects on anniversary of I-70 shutdown

Eric E. Vickers

Attorney, Minority Inclusion Alliance

St. Louis Metropolitan.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

,+W.+Bevis+Schock+and+James+Schottel,+Jr.+(seated)+claim+north-side+land+magnate+Paul+McKee+will+displace+residents+for+a+project+he+can%27t+possibly+pull+off..jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment