"When you're right, remarkable things happen."

Eric Vickers makes this statement between lengthy gaps of silence, pauses pregnant with emotional reflection on a life of service. For this edition of the RCE, we will examine this service in depth.

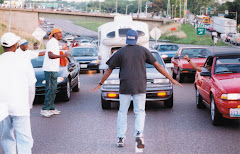

Vickers could be making this particular statement about many aspects of his career, but at this particular moment, as he's seated at the Bread Company in the Delmar Loop, he is referring to July 12, 1999, the day of the Interstate 70 shut down for minority inclusion in the highway's extension. "As the momentum gathered, it got to the point where you couldn't be down with the community and not be with the shutdown," he recalls of the final days leading up to the event. "That day, you could see the sense of victory. The different groups looked at each other and said 'Wow, we're really doing it. We said we were going to shut the highway down, and we're shutting the highway down.'" Vickers says that one of the long-term benefits of the shutdown was a training program for blacks looking for a career, or a career change. He says that he threatened a similar action to block the recently completed I-64 extension, if the Illinois Department of Transportation didn't increase minority participation and that this tactic resulted in the creation of a training program in Illinois. "Now, we're training brothers and sisters on both sides of the river. I love that." "[The I-70 shutdown] was also a moment of transition for me personally," he continues. "As Percy Green warned me, I had gone from being a lawyer to being in front. It wasn't that long after that my license got suspended. You can't really show a connection between the two, but, as Nikki Giovanni said, "When you do things on the cutting edge, you're gonna get cut." I didn't fight the suspension, even though I could have. I got a law license because of what an activist with a law degree could do. After I lost my license, I focused squarely on my activism. (Contrary to the perception of many, Vickers feels that his biggest accomplishment was the creation of City of St. Louis' Ordinance 68412 - made law is 1989 - which calls for 25% of labor hours to be performed by minorities and 5% by women. "I wanted something legal on the books," he says. {Vickers is currently using this law to highlight the apparent shortcomings in the Art Museum development.}

The drive to fight for equal treatment was cultivated during his upbringing. Vickers says that the biggest moment of his childhood was moving from East St. Louis to U. City. ’ÄúIt was like going into a whole new world. This was during the 60's. There was black power and black pride and during all of that we [Vickers has two brothers and a much younger sister] were dropped into this white enclave. It made you think about the inequities. It radicalized us.’Äù This ideological awakening soon found voice in a protest for more black representation at his new school, University City High. ’ÄúWe got up that morning, lined up in front of the school and didn't let anyone in," he remembers. "It shocked the entire University City community. From what I recall, Spring Break was soon after, and we met with the officials, stated our demands, and they met every one. We had some black teachers come in. We got some black books in the library. It makes you want to do more protests. You say to yourself 'Wow, this works.'"

Vickers furthered his education at Washington University and participated in the Coro Foundation fellowship program at Occidental College, through which he worked for General Dynamics. He was eventually hired in the personnel department at Monsanto. It didn't take long for the activism bug to bite. "They weren't promoting enough blacks into management, and they were firing blacks. I got the other black professionals together and we wrote a letter to complain." The newly formed group, calling themselves the Monsanto 15, didn't stop there. They took it among themselves to hire blacks, being undaunted when the bulk of the hiring responsibilities left Vickers’Äô hands. "We came in on Saturdays and I hired every brother and sister that came into that place. The unions hated us, because we were filling jobs that would have gone to their friends and family." Vickers feels that the struggle was worth it. "Thirty years later, I see some of them. They made it through, retired with full pensions."

Inspired by the sense of pride felt in successfully arguing on a fired employee's behalf at a hearing, Vickers decided to study law. He joined the Bryan Cave firm in 1981 and formed his own firm, Vickers, Moore and Wiest, in 1984. He started taking on outside jobs that allowed him to pursue his quest for social justice. He started representing MO-KAN, an advocate for minority-contractors, and fought for clients around the country.

Further notoriety would come when Vickers successful sued St. Clair County figure - head Francis Touchette, getting a woman who had refused to pay unofficially mandated fees to Touchette reinstated at her job. This victory would draw the attention of child hood friend Carl Officer, who was entering his third term as Mayor of East St. Louis. Vickers would become Officer's legal counsel. "What I love about Carl is that he had the idea of East St. Louis being independent. That's my boy," he says.

The feeling of admiration is mutual. Reached by phone, Officer recalls a time when he and Vickers were truly in dire straits. "A lawsuit had been filed against the city, with regard to the sewer project. We were doing the best we could with the time and resources we had, but, due to political pressure, the judge was encouraged to teach us a lesson. I noticed an inordinate number of police cars along the route, Illinois 15. I also noticed an inordinate amount of sheriff's deputies inside the court room. Bottom line is we were put in contempt of court. They would not accept a regular bond. They set a bond of $7,500 in cash, which I found peculiar because there were people in jail for murder who didn't need the bond money that we needed, but that was typical of the circuit court judges of that day. Luckily, our families were able to come up with the money and we were only there for a few hours. Also, a former representative/current sheriff moved us out of general lockup."

Carl continued, "He and I have had a few run-ins in the courts in Belleville and in federal courts as far away as New York City. I don't think that I have adequate words to describe my friendship with him. I admire him as a very principled gentleman. I think that he got a lot of that from his mother and his father. His father is a one of a kind individual that you'd want to model any son after and the kind of man you'd want your dad to be. I think that Eric didn't fall far from that tree. As an attorney, I have never met anyone as studious and relentless in pursuing his craft and his trade. He's been the kind of crusader to fight on behalf of those persons who did not have a legal voice, or did not have funds for a legal voice, or if it's someone looking at hundreds of years in an appellate situation, or if it was someone who did not have a job who was looking to get into a training program. He has never discriminated in his abilities as a lawyer to speak to the fact that he was a black man first. I have not had a better friend than Eric Vickers, and I'm certainly positive that I've not had a better lawyer."

In addition to supporting political figures, Vickers has fought to unseat them. In 1994, he vied for the seat of Congressman William Clay. "I thought that the Clay machine had become corrupt. What was remarkable to me about the campaign was the fear that people in the city had of him. Coming from the Eastside, I didn't have that fear of him. I had once respected him. He was a civil rights fighter and the white establishment was out to get him. But, at that point, he had been in there for 28 years and hadn't done anything for the last ten." Although his bid was unsuccessful, Vickers looks back at the experience fondly. "It was a fun a campaign. One day, he announced the opening of his headquarters at Delmar and Euclid. I bought myself an African cane, went to the opening, got in his face and challenged him to a debate, like Ali. He wouldn't do it, and one of his bodyguards lurched at me. It was caught on tape and all that weekend it was played on TV."

Most recently, with his law license regained in 2008, Vickers has taken his fight back to the courtroom. A golden opportunity arose when developer Paul McKee's plan to renovate the North side of St. Louis city was announced. "It had clear gentrification overtones," he says. Even though he respected the efforts of those who were planning protests, he felt that other action needed to be taken. He joined forces with fellow lawyers W. Bevis Schock, D.B. Amon and Hugh Eastwood to take action. Early last month, the circuit court ruled in favor of his clients, saying that the tax increment financing (TIF) package approved for the project was unlawful. "The record is bereft of evidence that anyone, anywhere has accomplished the feat of attracting new residents to core urban areas on a scale envisaged by defendants," read the opinion of Judge Robert Dierker, as quoted in The St. Louis Business Journal. "We got together and we kicked ass," says Vickers, with a gleam in his eye that matches his smile.

Vickers feels that victories such as this most recent one are fueled by his Muslim faith, a belief he entered while in law school. "It's the essence of me. I do the daily prayers, five or more. I've made the pilgrimage to Mecca. This Ramadan will be my 30th. I view the spiritual self like the physical self. You have to exercise it as much as possible in order to get the most out of it. That's what Islam requires me to do. The prayers, the restrictions, the fasting, it’Äôs all to get closer to God."

With regard to the future, Vickers is turning his attention to the juvenile court system, saying "I don't think that the system properly handles black youth. I think they are too quick to treat them like adults." In the broader scope, he says "I'm just getting started."

A tireless fighter is forging on.

Courtesy of Byron Lee, RCE

Attorney Eric Vickers

Defender of the weak and downtrodden

(I'll not hesitate to combine the power of lawsuit, protest,and blogging to go after oppressors).

Eric Vickers makes this statement between lengthy gaps of silence, pauses pregnant with emotional reflection on a life of service. For this edition of the RCE, we will examine this service in depth.

Vickers could be making this particular statement about many aspects of his career, but at this particular moment, as he's seated at the Bread Company in the Delmar Loop, he is referring to July 12, 1999, the day of the Interstate 70 shut down for minority inclusion in the highway's extension. "As the momentum gathered, it got to the point where you couldn't be down with the community and not be with the shutdown," he recalls of the final days leading up to the event. "That day, you could see the sense of victory. The different groups looked at each other and said 'Wow, we're really doing it. We said we were going to shut the highway down, and we're shutting the highway down.'" Vickers says that one of the long-term benefits of the shutdown was a training program for blacks looking for a career, or a career change. He says that he threatened a similar action to block the recently completed I-64 extension, if the Illinois Department of Transportation didn't increase minority participation and that this tactic resulted in the creation of a training program in Illinois. "Now, we're training brothers and sisters on both sides of the river. I love that." "[The I-70 shutdown] was also a moment of transition for me personally," he continues. "As Percy Green warned me, I had gone from being a lawyer to being in front. It wasn't that long after that my license got suspended. You can't really show a connection between the two, but, as Nikki Giovanni said, "When you do things on the cutting edge, you're gonna get cut." I didn't fight the suspension, even though I could have. I got a law license because of what an activist with a law degree could do. After I lost my license, I focused squarely on my activism. (Contrary to the perception of many, Vickers feels that his biggest accomplishment was the creation of City of St. Louis' Ordinance 68412 - made law is 1989 - which calls for 25% of labor hours to be performed by minorities and 5% by women. "I wanted something legal on the books," he says. {Vickers is currently using this law to highlight the apparent shortcomings in the Art Museum development.}

The drive to fight for equal treatment was cultivated during his upbringing. Vickers says that the biggest moment of his childhood was moving from East St. Louis to U. City. ’ÄúIt was like going into a whole new world. This was during the 60's. There was black power and black pride and during all of that we [Vickers has two brothers and a much younger sister] were dropped into this white enclave. It made you think about the inequities. It radicalized us.’Äù This ideological awakening soon found voice in a protest for more black representation at his new school, University City High. ’ÄúWe got up that morning, lined up in front of the school and didn't let anyone in," he remembers. "It shocked the entire University City community. From what I recall, Spring Break was soon after, and we met with the officials, stated our demands, and they met every one. We had some black teachers come in. We got some black books in the library. It makes you want to do more protests. You say to yourself 'Wow, this works.'"

Vickers furthered his education at Washington University and participated in the Coro Foundation fellowship program at Occidental College, through which he worked for General Dynamics. He was eventually hired in the personnel department at Monsanto. It didn't take long for the activism bug to bite. "They weren't promoting enough blacks into management, and they were firing blacks. I got the other black professionals together and we wrote a letter to complain." The newly formed group, calling themselves the Monsanto 15, didn't stop there. They took it among themselves to hire blacks, being undaunted when the bulk of the hiring responsibilities left Vickers’Äô hands. "We came in on Saturdays and I hired every brother and sister that came into that place. The unions hated us, because we were filling jobs that would have gone to their friends and family." Vickers feels that the struggle was worth it. "Thirty years later, I see some of them. They made it through, retired with full pensions."

Inspired by the sense of pride felt in successfully arguing on a fired employee's behalf at a hearing, Vickers decided to study law. He joined the Bryan Cave firm in 1981 and formed his own firm, Vickers, Moore and Wiest, in 1984. He started taking on outside jobs that allowed him to pursue his quest for social justice. He started representing MO-KAN, an advocate for minority-contractors, and fought for clients around the country.

Further notoriety would come when Vickers successful sued St. Clair County figure - head Francis Touchette, getting a woman who had refused to pay unofficially mandated fees to Touchette reinstated at her job. This victory would draw the attention of child hood friend Carl Officer, who was entering his third term as Mayor of East St. Louis. Vickers would become Officer's legal counsel. "What I love about Carl is that he had the idea of East St. Louis being independent. That's my boy," he says.

The feeling of admiration is mutual. Reached by phone, Officer recalls a time when he and Vickers were truly in dire straits. "A lawsuit had been filed against the city, with regard to the sewer project. We were doing the best we could with the time and resources we had, but, due to political pressure, the judge was encouraged to teach us a lesson. I noticed an inordinate number of police cars along the route, Illinois 15. I also noticed an inordinate amount of sheriff's deputies inside the court room. Bottom line is we were put in contempt of court. They would not accept a regular bond. They set a bond of $7,500 in cash, which I found peculiar because there were people in jail for murder who didn't need the bond money that we needed, but that was typical of the circuit court judges of that day. Luckily, our families were able to come up with the money and we were only there for a few hours. Also, a former representative/current sheriff moved us out of general lockup."

Carl continued, "He and I have had a few run-ins in the courts in Belleville and in federal courts as far away as New York City. I don't think that I have adequate words to describe my friendship with him. I admire him as a very principled gentleman. I think that he got a lot of that from his mother and his father. His father is a one of a kind individual that you'd want to model any son after and the kind of man you'd want your dad to be. I think that Eric didn't fall far from that tree. As an attorney, I have never met anyone as studious and relentless in pursuing his craft and his trade. He's been the kind of crusader to fight on behalf of those persons who did not have a legal voice, or did not have funds for a legal voice, or if it's someone looking at hundreds of years in an appellate situation, or if it was someone who did not have a job who was looking to get into a training program. He has never discriminated in his abilities as a lawyer to speak to the fact that he was a black man first. I have not had a better friend than Eric Vickers, and I'm certainly positive that I've not had a better lawyer."

In addition to supporting political figures, Vickers has fought to unseat them. In 1994, he vied for the seat of Congressman William Clay. "I thought that the Clay machine had become corrupt. What was remarkable to me about the campaign was the fear that people in the city had of him. Coming from the Eastside, I didn't have that fear of him. I had once respected him. He was a civil rights fighter and the white establishment was out to get him. But, at that point, he had been in there for 28 years and hadn't done anything for the last ten." Although his bid was unsuccessful, Vickers looks back at the experience fondly. "It was a fun a campaign. One day, he announced the opening of his headquarters at Delmar and Euclid. I bought myself an African cane, went to the opening, got in his face and challenged him to a debate, like Ali. He wouldn't do it, and one of his bodyguards lurched at me. It was caught on tape and all that weekend it was played on TV."

Most recently, with his law license regained in 2008, Vickers has taken his fight back to the courtroom. A golden opportunity arose when developer Paul McKee's plan to renovate the North side of St. Louis city was announced. "It had clear gentrification overtones," he says. Even though he respected the efforts of those who were planning protests, he felt that other action needed to be taken. He joined forces with fellow lawyers W. Bevis Schock, D.B. Amon and Hugh Eastwood to take action. Early last month, the circuit court ruled in favor of his clients, saying that the tax increment financing (TIF) package approved for the project was unlawful. "The record is bereft of evidence that anyone, anywhere has accomplished the feat of attracting new residents to core urban areas on a scale envisaged by defendants," read the opinion of Judge Robert Dierker, as quoted in The St. Louis Business Journal. "We got together and we kicked ass," says Vickers, with a gleam in his eye that matches his smile.

Vickers feels that victories such as this most recent one are fueled by his Muslim faith, a belief he entered while in law school. "It's the essence of me. I do the daily prayers, five or more. I've made the pilgrimage to Mecca. This Ramadan will be my 30th. I view the spiritual self like the physical self. You have to exercise it as much as possible in order to get the most out of it. That's what Islam requires me to do. The prayers, the restrictions, the fasting, it’Äôs all to get closer to God."

With regard to the future, Vickers is turning his attention to the juvenile court system, saying "I don't think that the system properly handles black youth. I think they are too quick to treat them like adults." In the broader scope, he says "I'm just getting started."

A tireless fighter is forging on.

Courtesy of Byron Lee, RCE

Attorney Eric Vickers

Defender of the weak and downtrodden

(I'll not hesitate to combine the power of lawsuit, protest,and blogging to go after oppressors).

,+W.+Bevis+Schock+and+James+Schottel,+Jr.+(seated)+claim+north-side+land+magnate+Paul+McKee+will+displace+residents+for+a+project+he+can%27t+possibly+pull+off..jpg)